当罗布·格罗斯 (Rob Gross) 站在物理学入门课的前面时,人群中没有人提问。

直到他开始展示他用 60 毫米望远镜和Explore Scientific GoTo 追踪器支架拍摄的照片。

“他们在课堂上从来不提问,也不说话,但当我展示我的照片时,他们就问了一大堆问题,”格罗斯说。“学生们完全不知道自己能做到,他们以为我的眼界很大。我告诉他们,‘不,我的眼界很小。’他们都很惊讶。”

格罗斯在佛罗里达大西洋大学任教,并在那里获得了天体物理学博士学位,他与许多在中年时开始研究天文学的成年人一样。

“我10岁的时候有一架便宜的望远镜,大概50美元。用来观察月球挺好用的,”他说,“但很快就坏了。”

天文学的种子要经过几十年才能发芽。

2020 年新冠疫情爆发时,和其他人一样,他有空闲时间,他通过网络填补了这些空闲时间。

“我住在佛罗里达州南部的一套公寓里。我以为光污染会让我没法进行天文摄影,”他解释道。在网上闲逛时,他偶然发现有人在高光污染环境下进行天文摄影。

他说:“这让我意识到我可以做到。”

他在天文摄影领域的第一步是行星成像。他用一台6英寸施密特-卡塞格林望远镜和他拥有的数码单反相机开始拍摄照片。

“我拍了一些挺酷的照片,但当时我还在考虑做别的,”他说,“我弄了一个带反光板的大支架,拍出来还行,但没那么好。”

进一步的阅读使他对深空天体(DSO)产生了兴趣。

“我在《云夜》节目里寻求建议。有人建议带上三脚架和单反相机,看看效果如何,”他说。2020年11月,在南佛罗里达州博尔特尔9号一处公寓庭院里,他确实这么做了,那里到处都是泛光灯。

“这就是我开始的方式,我想很多人也是这样开始的。”

用他的话说,他的照片拍得还不错。“我当时觉得‘还行,是的’,但我希望做得更好。”

研究让他想到了一种比星象跟踪器更坚固的小型便携式支架——Explore Scientific 的iEXOS-100 GoTo 跟踪器支架。

他开始将该支架与他的 DSRL 和 150 毫米至 600 毫米变焦镜头一起使用。

“为了校准极轴,我会用指南针,尽量让它指向北方,然后我会拍30秒的曝光照片,看看轨迹是往哪儿走的,”他解释道。“我会移动支架,再拍一张照片,直到对准为止。”

“效果不太好,照片不太好,相机和镜头也不太好,我也没有电脑来运行极轴校准程序。好几个晚上都校准不准,这让事情变得很困难——一切都很糟糕。我必须学会处理这件事。很难。”

为了将望远镜对准目标,他手动进行了背景校正——算是吧。他拍摄了DSRL液晶屏的照片,上传到nova.astrometry.net网站,然后查看网站上显示的望远镜指向的位置。然后,他移动望远镜,再次执行拍照/上传程序,直到对准目标。

他就这样操作了一年,直到他得到了一台微型电脑并开始使用具有自动解板程序的 Nina。

他说:“数据质量提高了很多。”这意味着他的照片质量也迅速提高了。

2021年末,他的生活变得忙碌起来,休息了大约一年。2022年末,他重新开始天文摄影,并购买了一台AT60ED望远镜、一台Player One Saturn相机和一台Antilla三波段滤镜。

虽然他在 DSRL 生涯中尝试过自动导航,但目前他还没有进行导航。

良好的极轴校准和 30 秒的曝光是他的日常工作。

“我跟别人争论说,30秒曝光比更长时间的曝光更好。对我来说,一朵云飘过来,我五分钟的曝光就毁了,”他说。虽然较短的曝光无法捕捉到精细的细节,但软件的改进使程序在提取细节方面有了很大的改进。

使用 GraXpert 3.0 程序中的去噪功能会产生很大的不同,尤其是在操作过程的早期使用时。

三年过去了,他的天文摄影之旅进展顺利。未来他可能会升级更大的支架,但iEXOS-100仍会留在他的装备库里,因为它便携且性能出色。

“我住在拍摄(天文)照片最糟糕的地方,但拍出来的照片还不错,”他说道,显然对自己的作品很谦虚。

他喜欢这些成果,也喜欢由此产生的电脑处理过程。他把这比作几十年前在暗房里冲洗胶片并制作照片。

“那时你必须等待结果,自己冲洗胶片,然后制作印刷品,这很有趣,”他解释道。

他没有特别喜欢的目标,他停下来思考了一下这个问题。“只要能拍到好照片就行,M42、礁湖星云、三裂星云之类的。”

回到课堂,他拍摄的这些照片确实让学生们大吃一惊,他称这些照片“还不错”。这些“还不错”的照片让原本沉默的学生变得活跃起来,充满好奇。

也许有一天,这些学生中的一些人会迷上天文摄影,开启他们自己的天文摄影之旅。这不会是罗布·格罗斯的旅程,但这段旅程无疑会受到他对天文摄影的热爱的启发。

•••

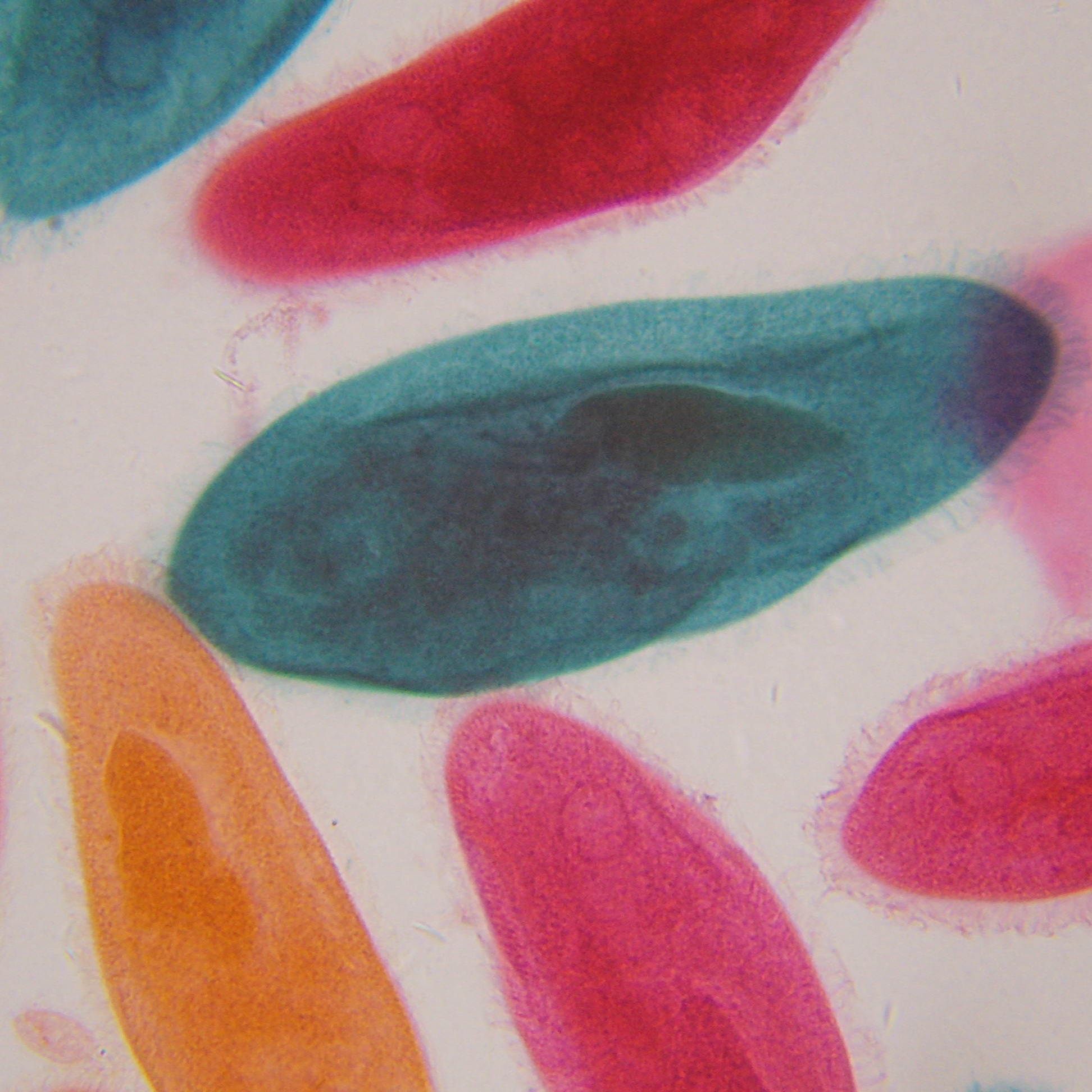

本博文中的所有天文照片均由 Rob Gross 在 Bortle 8/9 星空下拍摄。所有经过完全校准的图像处理流程使用了 GraXpert、Siril、Astrosharp 和 Affinity 软件。光学配置包括 iEXOS-100 支架、Saturn PlayerOne、配备 288mm 平场镜的 AT60ED 以及 Antila 三波段滤镜。

积分时间如下所列:

天鹅星云 – 6 小时

M42(猎户座星云):5.6小时

礁湖星云和三裂星云:5小时

面纱星云:9小时

针状星云:3.8小时

马卡林之链:6小时

加州星云:4.3小时

蟹状星云:2.2小时

1 条评论

Velibor

Very nice story and cool pictures. Didn’t know one can take such a detailed photos from the backyard, let alone light-polluted backyard. Kudos!

发表评论

所有评论在发布前都会经过审核。

此站点受 hCaptcha 保护,并且 hCaptcha 隐私政策和服务条款适用。